Multidisciplinary Systemic Methodology, for the Development of Middle-sized Cities. Case: Metropolitan Zone of Pachuca, Mexico

Volume 6, Issue 4, Page No 80-90, 2021

Author’s Name: Montaño-Arango Oscar1, Ortega-Reyes Antonio Oswaldo1,a), Corona-Armenta José Ramón1, Rivera-Gómez Héctor1, Martínez-Muñoz Enrique1, Robles-Acosta Carlos2

View Affiliations

1Autonomous University of the State of Hidalgo, Institute of Basic Sciences and Engineering, Academic Area of Engineering and Architecture, Hidalgo, 78556, Mexico

2Autonomous Mexico State University, Ecatepec University Center, Research and Postgraduate Coordination, Mexico

a)Author to whom correspondence should be addressed. E-mail: oswwaldoo@yahoo.com.mx

Adv. Sci. Technol. Eng. Syst. J. 6(4), 80-90 (2021); ![]() DOI: 10.25046/aj060410

DOI: 10.25046/aj060410

Keywords: Systemic approach, Middle-sized city, Situational analysis competitiveness, Model cities, Development

Export Citations

This paper analyzes the challenges a middle-sized city faces, particularly the Metropolitan Zone of Pachuca (MZP), which has not had the expected development given its current geographic, competitiveness, and crisis circumstances. The research proposes a systemic methodology for the analysis of the aforementioned Metropolitan Area. It emphasizes its internal and external behavior, the competitive environment of neighboring cities, conditions of middle-sized cities in Latin America, and the trends of model cities worldwide. The study identified the factors limiting their development and the competencies that can be used based on the opportunities, limitations, and perspectives. The result was a situational temporality matrix of the initiatives according to the impacts, which will specify the necessary characteristics to establishing strategies and the compatibility of the perspective of the Metropolitan Area of Pachuca for the transition towards the model of growth called New Urbanism.

Received: 05 May 2021, Accepted: 12 June 2021, Published Online: 10 July 2021

1. Introduction

Nowadays, there are several questions about the capacity of middle-sized cities to face the phenomenon of globalization successfully, and the way they get inserted and participate in it. These peculiarities might reflect a difference in terms of competitiveness and the assessment of its meaning, to lay the basis for decision-making when public policy design and planning [1]; this enables to forge development and welfare in terms of the collective needs and the environment in which middle-sized cities interact [2]. Likewise, in [3], it is mentioned that these cities have advantages over large cities, which is why they should perform essential functions for territorial balance.

Cities are not only spaces for the production of goods and amenities, but places that generate knowledge, create new ideas that define new forms of social relationships. It is essential to understand their process of the conformation since it marks their daily life or, in some cases, subsistence, also the rate of growth, well-being, and progress. Their analysis, consequently, is not exclusive to a particular discipline. It is necessary to incorporate different approaches for their better understanding, because into them dwell more than 50% of the population in the world, and in the case of Mexico, more than three-quarters of the population [1], [4] and [5].

This research addresses an evaluation of the connotation of development in middle-sized cities through a systemic methodology. They demand urgent evolution, which considers their competitive environment and the formalization of instruments to articulate current elements of the territory. The challenge is even more significant when incorporating the best practices of the competitive mean due to the restrictions derived from weaknesses and threatens. Besides, there are local specifications which difficult the transition to modern cities. Therefore, it is important to plan their future according to the guidelines brought out by the study.

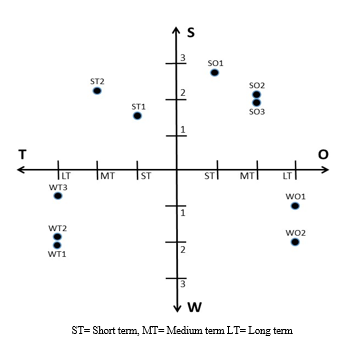

We present a temporary positional matrix with the highlights emanated from the SWOT and PESTEL analysis, composed of four quadrants where the initiatives point out priorities and strategic lines to define an urban development project according to the temporary spatial horizons.

1.1. The concept of development as a guideline for the use of the territory

Faced with the new environment for the development and use of the territory of cities Sesmas [6], sets three main scenarios: contextual (integrated by the processes of globalization and decentralization), strategic (linked to a new organization and territorial management), and political (regarding a modern State, capable of territorial leadership, via the different policy instruments) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Scenarios that define the territory

Figure 1: Scenarios that define the territory

Source: Author’s elaboration based on Sesmas [6]

On the other hand, the concept of development is a frame of reference that gives the general guidelines that have an impact on the conformation of the territory and competitiveness. Economics was the first discipline to use this idea, almost as a synonym for economic growth. However, concerning Geography, it acquires social nuances that make it closer to the ‘non-economic’ needs of populations [7].

The word development comes from the Greek α νά πτυξη (anaptise) and means “unfold” or also “discover”. Therefore, development is a set of potentialities that each social group possesses and must reveal. This etymological interpretation of the concept shows that progress and welfare of the population do not depend exclusively on external factors, but on latent endogenous potentialities which await to be “brazen” or “discovered” [7] and [8]. In this regard: “If ultimately we consider development as expanding the capacity of people to perform activities freely chosen and valued, it would be entirely inappropriate to exalt human beings as instruments of economic development” [9].

Therefore, in the search for development, the construction of utopias is essential since the transition might, at some point, go through one crisis [10]. In this way, a fundamental premise is to build a guideline that enables coexistence, socio-economic organization and competition of space, within a broad and global structural coherence.

1.2. Growth approaches for the development of cities worldwide

Since 1987, when the Brundtland Report established the concept of sustainability and sustainable as an adjective of development and, as part of the global lexicon [11], several tendencies arose about it and its focus on human settlements which allude to three approaches: smart growth, new urbanism, and ecological city.

Approaches to smart growth and new urbanism have become words of recognition incorporated in the United States (U.S.) into development planning goals and policies. Also, ecological cities have been less influential in the U.S. than the other two approaches [12]. However, in other parts of the world, this approach has received much attention to developing urban areas, particularly in Europe, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand [13] and, recently, Asia [14].

Smart growth represents an attempt to curb the expansion and its physical expression, ought to be integral and address issues such as protection of natural resources, diversity of homes – where the economic development depends on local capacity – and citizen participation [15].

Regarding New Urbanism, it is a design that, is oriented towards what represents a community architecture that is more humanized in scale and character [16] and [13] centering on tangible assets, urban landscapes, and design districts to improve the quality of life. It is composed of mixed uses, of a more compact configuration, a consistent and sensitive architecture to its place [17], abundant common open spaces (both: functional and natural) and, friendly as well as pedestrian-oriented inner circulation [18]. Multidisciplinarity is a relevant affair in New Urbanism in the U.S. [19]. Its processes include planners, developers, architects, engineers, government officials, investors, and community activists, as well as general stakeholders. Its goal is developing communities that do not exceed the limits of nature for livelihood, which is the load capacity. The gathering of these elements supports the concept of ecological cities. Thus, Ecocity Builders [20], – defined colloquially as Eco-city – in terms of land use policies, have the following objectives: to maximize urban density, reduce energy consumption, protect biodiversity, reduce travel distances and maximize options of transportation. Similarly, its principles are a way of giving shape and meaning to the concept of sustainability.

Based on the above, the following are crucial elements for the development of sustainable city planning since they allow carrying out result evaluations of the different policies implemented [21]:

- Level of urban competitiveness.

- Importance of services and industry with high degrees of innovation.

- Demographic changes

- Growth of middle-sized cities.

- Growth and, metropolitan concentration (sustainability).

- Decreasing urban-rural differentiation.

- Growth of the informal sector.

- Urban governance.

- Climate change and, city matters.

In [22], the author affirms the need for political will to create tracking systems based on precise indicators such as those in Dongtan, China or, Cambridge, England that have become icons of sustainable and competitive development; highlighting as well Stockholm, Sweden, and Hamburg, Germany, for being awarded in 2010 [23] and 2011 [24] respectively, for fulfilling the indicators of the European Green Capital Award.

1.3. Middle-sized cities

In recent decades, medium-sized towns have experienced a rapid sweep of spatial growth, changing their growth patterns in terms of coverage, land use, and fragmentation of the urban landscape, where it is substantial to understand urban growth processes and their relationship with sustainability. By the year 2025, 13.6% of the population will live in megacities, and 42.4% in middle and small cities, which will require more resources for its operation, with the premise that currently, they have less technology and means to mitigate pollution and cope with urban dynamics, which attenuates their management effectiveness [25].

Medium-sized cities currently seem to constitute a suitable means that promote a development that adapts to new interpretations. On the other side, facing the risk of increasing gaps between large metropolitan and rural areas seem to be the ideal instrument for achieving more balanced development in the territory [26].

Thus, according to Ganau & Vilagrasa [27] and Brunet [28], intermediate cities present defining features: 1) they are non-metropolitan centers, but they have sufficient critical mass and the will to transform themselves and be well equipped; 2) they are nuclei that can act as intermediaries between the big city and rural spaces and 3) they might be capable of generating growth and development in their immediate surroundings and of balancing the territory against metropolitan macrocephaly. Bellet and Llop [29] point out that these can act as providers of specialized goods and services, as well as centers of social, economic, and cultural interaction for their environment. Local governments of middle-sized cities present a large number of interconnections with their surrounding territory and other cities. With the pressure for urbanization, which comes hand in hand with progress, affecting their peripheries and localized municipalities near the big cities [30], becoming the reason why the challenges of local governments in middle sized cities on urban planning are very complex [31].

1.4. Growth of Latin American medium cities

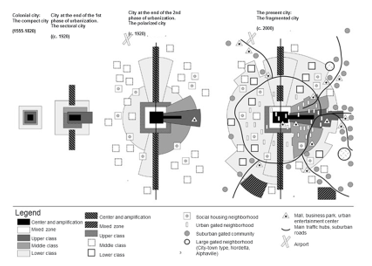

In the Latin American case, the growth of cities has been in cycles. Figure 2 shows how they changed from a very compact territorial body to a sectorial perimeter and from a polarized city to a fragmented one [32]. In the last phase, globalism had a vast influence on them, reflecting dramatic changes in their urban structure and development [33]. This circumstance made it necessary to expand the traditional model for urban development, establishing new phases [34].

In [35], the author refer that physically, growth in Latin American cities has been quite peculiar. In the middle of the ’90s, its expansion was oil stain type. That is, in continuous extension. At present, most cities have adopted scattered growth patterns throughout the territory, generating an uncontrolled peri-urbanization [36] featuring this process -due to fast changes in the city- with lack of regulation.

New developments began in rural areas [37], where the value of the land was lower along with urbanization would generate more added value. But as it did not have any supervisory body other than the market itself, the quality concerning the new developments began to decline considerably, configuring new areas of cities with much more precarious standards than the previous ones. These new difficulties bring a profound process of crisis and transformation which, comes mainly from the necessity of adapting to new national economic and social conditions and also to the recent characteristics of urban development [38]. In this regard, [39], mention that regional development in Latin America has led to a vaster expansion and diversification of the system of cities because between 1950 and 2000, it went from 314 to 1851 towns with more than 20,000 populations. This more complex urban network forms a social and territorial base more prone to regional development, detecting that medium-sized cities (50,000 to 500,000 inhabitants) and small cities (20,000 to 50,000 inhabitants) are expanding rapidly in terms of nodal multiplication, which confirms the trend towards a more robust and complex urban system.

Figure 2: Transition of the development models of the Latin American City

Figure 2: Transition of the development models of the Latin American City

Source: [33]

The development analyses reflect that the urbanization of cities allows greater prosperity in society (table 1).

Table 1: Level of urbanization and gross domestic product

| Country | Level of urbanization

2010 |

GDP per cápita

USD |

| Argentina | 90,0 | 9.952 |

| Bolivia | 62,0 | 1.134 |

| Brasil | 87,0 | 4.375 |

| Chile | 89,0 | 6.248 |

| Colombia | 75,0 | 2.879 |

| Ecuador | 67,0 | 1.705 |

| Guatemala | 50,0 | 1.700 |

| Haití | 50,0 | 391 |

| Jamaica (2007) | 54,0 | 3.028 |

| México | 78,0 | 7.116 |

| Perú | 72,0 | 2.990 |

| Venezuela | 94,0 | 5.969 |

Source: [40]

In [41], the author mentions that middle-sized cities have the challenge of assuming a decisive role when it comes to redistributing better progress in the countries, which should have the function of articulating large cities and those of provincial rank, besides, to have a substantial impact on economic integration and territorial cohesion.

1.5. Growth of middle-sized Mexican cities

Mexican cities, as all the Latin American ones, have been characterized by having an accelerated growth of their urban areas, but not of urbanization. For many decades the new spaces incorporated into Mexican cities were occupied by their inhabitants with minimal services and infrastructure, and, in some cases, they were just nonexistent.

Each city solved this relevant gap of services and infrastructure over time according to their urbanization processes [42].

Thus, a centralist-productive structure propitiates changing migratory flows, which at the same time; delimit the short existence of middle-sized cities. Besides, policies to support middle-sized cities have been unsuccessful. The Mexican government created a priority stimulus for medium-sized and small towns to counteract the weightiness of Mexico City, Guadalajara, and Monterrey, but it did not provoke the expected territorial deconcentrating, demonstrating its failure. Although the number of medium-sized cities increased, it was not due to policies for a territorial reorganization of land, but growth logics [43].

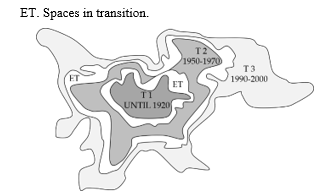

In [44], the author points out that there is not enough information to analyze the development of medium-sized cities, so he proposes a scheme by growth zones through development time, identifying three “T” periods (figure 3):

(T1) Space developed until 1920, which is an urban space that represents the origin of the city. A regular layout of large properties, high construction density with predominantly commercial and service land uses. But, with some embedded sectors like housing.

(T2) 1950 to 1970. Space developed during periods of high rates of urban population growth in Mexico. At first, the area probably lacked infrastructure, but it incorporated it over time until achieving all the services and infrastructure.

(T3) 1990 to 2000. The features of this period are urban spaces with new subdivisions of low-income housing; warehouses, and industrial parks, large peripheral roads, and access to the city.

- Spaces in transition.

Figure 3. Characteristic periods of the urban space of Mexican middle-sized cities.

Figure 3. Characteristic periods of the urban space of Mexican middle-sized cities.

Source: [44]

In [45], the structural model of mid-sized cities in Mexico relies on the colonial urban layout (checkerboard shape), describing that the development phases occurred in the following way: Traditional city, Fragmented city, Regional Conurbation Metropolis. In this last phase, there is no spatial unit in the metropolitan area, where the urban elements were interwoven with each other and arranged on top of them.

Mexican cities must follow the policies established by three federal laws: The General Law of Human Settlements (LGAH), the Housing Law, and The General Law of Ecological Balance and Environmental Protection (LGEEPA). The LGAH delegates the responsibilities of design and urban planning to the municipalities, limiting itself to establishing procedures for development plans.

The outlook for the growth and development of cities for the coming years seems encouraging. That is due to the nascent policies and programs of the sector. However, it will depend on their proper implementation, coordination between the different political actors, federal and local institutions, as well as the continuity between the administrations, pointing to 1) the urban planning, 2) land use planning, 3) management, 4) implementation, 5) monitoring and control and, 6) improvement.

1.6. Metropolitan Zone of Pachuca (MZP)

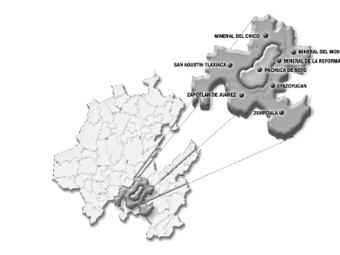

The MZP is south of the state of Hidalgo. It is a middle-sized city in the range of 500,000 inhabitants and, it communicates with Mexico City through Federal Highway number 85. Table 2 shows the municipalities it comprises and figure 4 the delimitation of the Municipalities of the MZP.

Table 2. Characteristics of the municipalities that make up the MZP

| Municipality | Population | Area (ha) | % Area |

| Epazoyucan | 14,693 | 14,070 | 11.77 |

| Mineral del Monte | 14,640 | 5,339 | 4.47 |

| Mineral de la Reforma | 150,176 | 11,393 | 9.53 |

| Pachuca de Soto | 277,375 | 15,398 | 12.88 |

| San Agustín Tlaxiaca | 36,079 | 29,713 | 24.85 |

| Zapotlán de Juárez | 18,748 | 11,686 | 9.77 |

| Zempoala | 45382 | 31,962 | 26.73 |

| Total | 557,093 | 119,561 | 100.00 |

Source: Author’s elaboration based on [46]

Figure 4: Delimitation of the Municipalities of the MZP [46]

Figure 4: Delimitation of the Municipalities of the MZP [46]

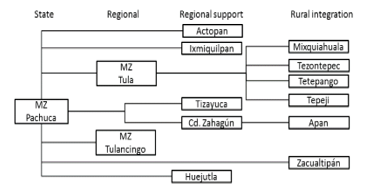

According to the National Urban System [47], the level of urbanization of the state of Hidalgo is defined by the hierarchy, location, and degree of functional integration of each city, as shown in figure 5.

Figure 5: Urban System of the State of Hidalgo from the MZP

Figure 5: Urban System of the State of Hidalgo from the MZP

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on [47]

1.6.1. Trends in urban expansion

The rapid growth of the MZP can be seen in the spread of its territory, indicating greater incorporation of hectares for urban purposes. In 2000, the conurbation area was 7,918 ha., which increased to 14,907 ha. in 2010. It is an increase of 6,989 ha. and represents an 88.2 % rise. The type of urban expansion manifests itself from two modalities:

- Expansion by informal growth

Those made in irregular human settlements, which are in areas subject to natural hazards, for example: on steep slopes, in floodable areas, or vulnerable soils. On the other hand, the irregularity condition prevents them from having amenities, such as water, drainage, electricity, paving, garbage collection, lighting, surveillance, or adequate public spaces furthermore legal land property affairs. This situation contributes to the fact that their inhabitants present critical social lags, low school levels, poor health services, overcrowding, and deteriorated housing quality.

- Expansion in disjointed housing complexes in the urban area continues.

Another type of recent urban expansion is the creation of housing facilities located in the urban periphery, characterized by the massive construction of housing, under one or two designs of predominant typology, whose promotion is through national institutional housing funds (Infonavit and Fovissste) or other organizations, to the eligible population. Although this housing estate has a better quality of construction and architectural settlements, many of them have problems in terms of the provision of public services such as regular water supply, public lighting, surveillance or -due to their remoteness-, public transport, which represents higher expenses for its inhabitants and a reduction in the quality of life. It does not imply that occasionally, some of these subdivisions are in areas subject to natural hazards. For example, in flood-prone zones, with consequent affectations for the inhabitants and the buildings they inhabit.

These growth patterns have different effects regarding municipal procurement:

- They represent relevant increases in their population, with the consequent escalations in demand for public works, goods, and services.

- They imply an increase in the maintenance and expansion of urban infrastructure and public facilities.

- The lack of mechanisms for using the land and urban planning caused the habitation of areas at risk or productive zones. It translates into more work and more actions for their maintenance.

- Irregular urban sprawl brings conflicts around the property, especially if there are no property titles or complete property regularization processes.

- Municipal administrations face more limitations at getting resources when there are no up to date instruments for collecting local taxes related to property.

1.6.2. Land ownership regime

There are in the MZP a lot of communal agricultural centers that comprehend to 109.375 ha. several of these suburbs are near urban centers, where a big part of urban sprawl relies on vast extensions of minor lands known as “ejidos” which are a legal figure in the Mexican normativity that allows groups of small owners to use the land for no urban purposes:

- The location of the “ejidos” where the proportion of parceled land is in the proximity of urban centers, represents possibilities of alienation for urban uses. Besides, there is some delay in the operation of public property records, which allows registering the “ejidos” as private property and not as collective goods, which generates irregular mechanisms for land buying and selling.

- The territorial expansion of urban “ejido zones” and the lots destined for human settlements on communal lands may also constitute forms of conversion to urban land or, for the regularization of illegally established human communities [48].

1.6.3. Regulatory framework

The institutional action on urban planning derived from the publication in Mexico of the General Law on Human Settlements of the year 1976 and, the establishment and operation of the Ministry of Human Settlements and Public Works, promoted the development and publication of the State Program for Urban Development and Territorial Planning of the State of Hidalgo (PEDU and OTEH), as a pioneering initiative of the urban and regional planning system, undertaken in Mexico as part of the national policy on the territory. Its premises highlight the need for regeneration and exploitation of natural resources in the context of urbanization, the need for prevention and risk and vulnerability in cities (urban emergencies); to promote an adequate public administration for the urban development, the need for participation of the society on urban issues and, promoting financing for public works specifically in the municipal order.

Thus, the contributions of regulatory scope, stand on the adequacy of the public administration in the levels of municipalities and the state, regarding urban development, infrastructure to support the supply of energy and, the need to establish ways to promote the financing of municipal works. However, the dynamics and social and demographic structure offer a different picture, forcing to define specific policies to face enormous challenges such as the urbanization in the southern part of the state, where the MZP is.

The urbanization process of the Valley of Mexico in the State of Hidalgo is the most evident influence that obliges to rethink the territorial strategy. As a derivation of this reality, are critical situations such as connectivity, occupation of land without aptitude for urban development, and the consequent increase and sustained, long – term, costs of urbanization aside from considering the capacities and abilities that municipal governments must have to face their constitutional responsibilities in terms of development and freedom [49].

1.6.4. Cities within their competitive environment

The MZP competes for resources, investments, users’ attraction, and infrastructure with the metropolis of Querétaro, Mexico, Puebla, and Tlaxcala. These cities are megalopolis -except for Tlaxcala-, which have grown better and have absorbed over time the small towns and surrounding municipalities. The expansion has been irregular because those cities have functioned as axes of development in the country, altogether with their spatial distribution of economic activities and population [50].

On the other hand, medium-sized cities have taken on the great importance, because they became escape valves for the growth of large cities, which, in the case of the MZP, has been forced to work as a bedroom city and has had to adapt to the policies and strategies of big cities. This brought the construction of large residential areas south of Pachuca City and the municipality of Mineral de la Reforma.

The MZP connects with the highway Arco Norte (North Arch) that communicates with the main cities of Central Mexico: Tlaxcala, Puebla, and Queretaro; and also allows to reach the port of Veracruz and, towards the north, with the most industrialized cities in the country.

The IMCO competitiveness index [51] ranks the villages where the MZP competes in the region as follows: 1. Mexico City; 3. City of Queretaro; 23. The towns of Puebla-Tlaxcala and, 47 City of Pachuca, which is considered a middle-sized city with a medium-low level of competitiveness. Best-rated cities stand out for their diversified economy for hosting large companies, having socially responsible companies; good quality urban services; good quality universities; use of financial services, airlines and, bus lines. Nevertheless, they face greater insecurity, high population density, higher costs for public services, and traffic congestions.

Therefore, this study’s purpose was to characterize transitional strategies towards the structural basis for adopting the model known as New Urbanism. Its importance relies on identifying the main elements that allow doing a benchmarking with neighboring cities, which we did through the systemic approach.

2. Methods

According to [52], a systemic approach is necessary to study cities since they are complex adaptive systems. Meanwhile in [53], the author indicate that urban environments have socio-environmental variables that should be studied systemically. The Systems Approach considers the whole system in the search of means to achieve a goal and its choice [54] and [55]; it represents optimization and efficiency in a network of complex interactions within a dynamic environment, likewise to study cities. It relies on interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary studies. It also considers the Cybernetic approach, which is a resource of transdisciplinarity which serves to distinguish the two main subsystems at any system: the management or driver and, productive or conducted, comprising the fundamental relationships of these: of information and those of execution [56].

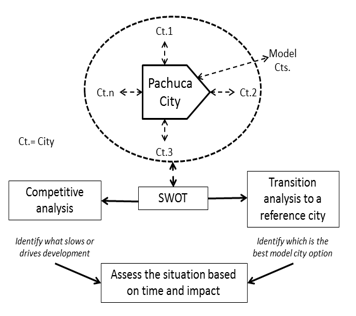

Figure 6. Multidisciplinary Systemic Methodology for the study of Middle-sized Cities

Figure 6. Multidisciplinary Systemic Methodology for the study of Middle-sized Cities

Source: Author’s own elaboration (2021)

Thus, [57] describe that, in the dawn of the XXI Century, people, regions, and cities face new challenges that require interventions based on multidisciplinary methodologies which enable to project and try to control facts, because the challenges are too many and too powerful to let them happen randomly. The conceptualization of the context, the diagnosis, the planning, and the operation, result in this way, fundamental tools to achieve the sustainability of the development of the current and future regions and cities asides to ensure equity and participation of the regional society. Figure 6 shows the systemic methodological design of the study.

Table 3: Impact of MZP with its environment

| Strengths (S) | Weaknesses (W) |

| 1. Growing and articulation of the primary communication routes.

2. Equipment availability at different service levels. 3. Development of industrial parks and the promotion of innovation. 4. Stable political system. 5. Availability of natural, human, and cultural resources. 6. Sufficient supply at different educational levels. 7. Rating of the MZP as a safe zone. |

1. Obsolete regulations to use the territory (territorial ordering) at the state, regional, and municipal levels.

2. Regulatory framework out of date of urban growth at different levels (national, regional, metropolitan, suburban, population, and areas of interest). 3. Growth over “ejido” zones and conflicts over land ownership and use. 4. Regional inequity in the provision of basic services. 5. Low quality of life. 6. Poor economic diversity. 7. Stable but reduced work market. 8. Poor management of political actors. 9. Insufficient inputs and suppliers. |

| Opportunities (O) | Threats (T) |

| 10. Location near the Valley of Mexico.

11. Proximity to highways, to industrial and energy infrastructure corridors nationwide. 12. Location within the state of equipment and infrastructure of regional and national importance. 13. Application of national and international standards and best practices regarding development. |

14. Territorial expansion of the metropolitan area of the Valley of Mexico.

15. Increased competitiveness of near metropolitan areas (State of Mexico, Queretaro, Tlaxcala, Puebla). 16. Better management capacity in other entities to expedite the location of large companies. |

| Source: Author’s own elaboration (2021) | |

We identified and analyzed relevant facts to establish grounds for a general plan of development and growth. We took as a basis the framework of multifactorial analysis known as PESTEL to categorize the Political, Economic, Socio-cultural, Technological, Ecological, and Legal fields. We also used the SWOT competitiveness analysis to establish the Strengths (S), Weaknesses (W), Opportunities (O), and Threats (T) of the MZP, interrelating Strenghts-Opportunities (SO), Strenghts-Threatens (ST), Weaknesses (W) and Weaknesses-Opportunities (WO). Based on both, a temporal scheme by quadrants is proposed, to identify the impacts and times necessary in acting on competitive priorities, which facilitates their study to identify the possibilities and restrictions inherent to development from the perspective of New Urbanism.

We applied the systemic approach and multidisciplinary analysis for the methodological design. We validated instruments and collected information through the technique of transdisciplinary consultation with experts and random selection. We also used brainstorming and comparative analysis techniques to evaluate the competitiveness of the MZP and determine the transition path to the reference model city.

3. Results

This section may be divided by subheadings. It should provide a concise and precise description of the experimental results, their interpretation, as well as the experimental conclusions that can be drawn.

Table 3 shows the cross-impact of MZP with its environment. To set the relevance of the impacts, the following values were used: 3 = High impact, 2 = Medium impact, 1 = Low impact and 0 = No impact.

Table 4 describes the results concerning the strategic direction pro-posed as a result of the analyzes carried out.

Table 4: Crossing of impacts SO, ST, WO and WT

| O1 | O2 | O3 | O4 | T1 | T2 | T3 | |

| S1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 0 |

| S2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| S3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| S4 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| S5 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| S6 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| S7 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| Sum | 18 | 16 | 13 | 15 | 12 | 16 | 2 |

| W1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| W2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| W3 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| W4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| W5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| W6 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| W7 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| W8 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| W9 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Sum | 14 | 9 | 9 | 21 | 21 | 19 | 11 |

Table 5: Impact analysis

| O | T | |

|

S |

SO 1

Possibilities of improving regional articulation around the Valley of Mexico and the North Central and Gulf of Mexico regions. SO2 Possibilities of attracting large companies due to their proximity to communication routes, qualified workforce, and availability of infrastructure. SO4 Development of conditions to apply national and international benchmarks and best practices in the different fields of competitiveness, depending on the type of city under view. |

ST 1

The development of industrial parks, political stability, and security of the area enables comp anies to consider the MZP as an option for its establishment, which can attenuate the growth of the metropolitan area of Mexico City. ST2 The expansion of the network of communication routes in an environment of political stability and security makes the MZP more attractive compared to the metropolitan areas considered.

|

|

W |

WO 1

The adaptation of the regulatory framework and more effective government management will facilitate taking advantage of the proximity to the Metropolitan Zone of the Valley of Mexico (MZVM). WO4 More effective government management, the existing communication network, and the strategic location of the MZP concerning energy infrastructure will allow its promotion as a supplier of the industrial corridors of the central region of the country.

|

WT 1

Through effective government management, it is necessary to adapt the regulatory framework that contemplates systemically, all factors of the territorial organization to expedite the permits for the establishment of companies. WT2 Through effective government management, it is necessary to adapt the regulatory framework that considers all the factors of territorial ordering and urban expansion; that makes the MZP attractive for the establishment of companies compared to other areas. WT3 The region has not been favored by companies that have sought a place to establish themselves and have selected other alternatives. That is the reason why it is relevant to review the management, the policies adopted, the land regulation, adaptation of the regulatory framework, and the leadership of political actors.

|

Source: Author’s own elaboration (2021)

From the analysis of tables 4 and 5, we highlight that the SO quadrant is the one with the highest impact (62 points); which indicates the ability to develop offensive strategies with the limits in ST (30 points) since there are no elements enough to counter threats from the competitive environment. Therefore, government management, the periods of government (which truncate the learning curve), the long-term planning (support targets), quality infrastructure, and the regulatory framework are the points that need a reorientation to detonate development and growth in the region.

For the PESTEL analysis we identified each of the perspectives and the level of impacts based on threats and opportunities, as shown in Table 6.

In this analysis we point out that the highest weaknesses occur in the legal and ecological aspects, with better positive effects on the economic and socio-cultural areas. However, the resulting graph shows a stronger trend in positive aspects, which favors the development possibilities of the MZP, based on its socio-cultural, technological, and economic advantages. Figure 8 shows the initiatives arising from these analyses, which consist of four quadrants, according to impacts and the degree of priority we identified.

Table 6: PESTEL

Source: Author’s own elaboration (2021)

Source: Author’s own elaboration (2021)

ST= Short term, MT= Medium term LT= Long term

Figure 8: Situational timing for SWOT analysis initiatives

Figure 8: Situational timing for SWOT analysis initiatives

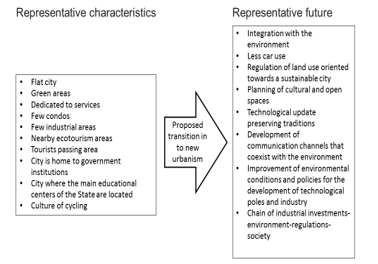

Figure 9: Proposed transition for the Metropolitan Zone of Pachuca (MZP)

Figure 9: Proposed transition for the Metropolitan Zone of Pachuca (MZP)

Figure 9 shows the transitional projected strategic lines of action identified for purposes of valuation and relevancy to establish the guidelines and spatiotemporal horizons for the set up with the proposed urban development of the MZP. We should note that, in the analyzes, the SO quadrant is limited (3 opportunities to work) concerning the other three quadrants (7 distractions). It represents the requirement to direct and adequately manage the necessary resources to strategically counteract the threats and weaknesses we exposed in the study.

The connotation of development urgently requires evolution, considering the formalization of instruments capable of articulating current glimpse in the territory. However, the challenge is tougher when attempting to incorporate the best practices of the sphere because of restrictions on the weaknesses and threats. In addition to that, some peculiarities forecast urgent attention, for example, land tenure, provision of services, conceptualization, and design of the society of the MZP along with equipment and transportation, which are only part of the current joint.

The MZP is currently moving into modernization, so it is important to plan its future according to this study. A primary approach consists of moving into the Model of New Urbanism since its innocuous characteristics are necessary for this option, as exposed in figure 9.

4. Conclusions

The lack of tools to identify and set the trend in urban development and land use show the urgency to define ways to conceptualize and implement the target image of a middle-sized city as required in the MZP, considering international references in an adequate dimension, for their implementation at different levels of analysis, planning, and execution.

The international benchmarks provide alternatives to the conditions in the conformation of urban clusters that could be useful. However, each territory-region has its dynamics, which is in the function of the environment in which it competes. Therefore, it is necessary to establish the magnitude of the implied factors, including their elements and environmental aspects that interact to reach the development.

The intense relationship and dependence that the MZP has with Mexico City, which is the largest in the country, represents a major challenge, where the management of the territory must obey a planning around urban development and land use, under a context of competitiveness, with a perspective towards sustainable development.

The planning of the MZP, as has been done so far, has led to a time lag in the face of a constantly changing territorial and urban reality, it is necessary that there be proper management to adapt to the dynamics of modern times.

The systemic treatment, -based on a methodology that involves the study area, referents of model cities, competitiveness of surrounding cities, treatment of feedback through the PESTEL and SWOT matrices-, gives a reasonable approach to the status and support for decision-making, which is linked to the situational temporality of the actions based on the analysis of the impacts, which is vital to project the growth and development of a middle-sized city.

Thus, the preceding, applied to the Metropolitan Area of Pachuca, allowed defining the characteristics necessary to transition to the New Urbanism Model.

As limits for future studies remain the changing environment of the MZP due to political trends in the different government levels and the inner dynamics of the mean, which depends on the features of the territory where it competes, implying its resources in the search for development.

Author Contributions

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

- E. Cabrero, Retos a la Competitividad Urbana en México. México: Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas (CIDE), 2013.

- IMCO, Índice de Competitividad Urbana 2010: Acciones Urgentes para las Ciudades del Futuro, Instituto Mexicano para la Competitividad A. C., 2010.

- M. Garrido, J. Rodríguez, E. López, “El papel de las ciudades medias de interior en el desarrollo regional. El caso de Andalucía”, Boletín de la Asociación de Geógrafos Españoles, 71, 375-395, 2016. doi: 10.21138/bage.2287

- G. Garza, M. Schteingart, Desarrollo urbano y regional. El Colegio de México, 2010.

- F. Carrión, La ciudad construida, urbanismo en América Latina. Facultad Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales (FLACSO), 2001.

- R. Sesmas, “Reseña-Crecimiento económico y desarrollo social: una contribución al estudio del territorio”, Economía, Sociedad y Territorio, 11(35), 265-271, 2011. doi: 10.22136/est002011127

- G. Berton, “Apreciaciones conceptuales del término desarrollo”, Huellas, 13, 192-203, 2009.

- C. Torres, “Planeación y Desarrollo Territorial, Metodología para su diseño”, Austral de Ciencias Sociales, 3, 141-158, 1999. doi: 10.4206/rev.austral.cienc.soc.1999.n3-10

- A. Sen, Ética y desarrollo: la relación, BID, 1998.

- J. González et al, “La territorialización de la política pública en el proceso de gestión territorial como praxis para el desarrollo”, Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural, 10(72), 243-265, 2013. doi: 10.11144/Javeriana.cdr10-72.tppp

- E. Minea, “Territorial Attractiveness – A Long-Term Issue for Public Policies”, Juridical Current Journal, 58(3), 101-110, 2014.

- T. Saunders, “Ecology and community design: lessons from Northern European ecological communities” Alternatives, 22(2), 24-29, 1996.

- J. Edwards, M. Edwards, “How Possible is Sustainable Urban Development? An Analysis of Planners’ Perceptions about New Urbanism, Smart Growth and the Ecological City”, Planning Practice and Research, 25(4), 417-437, 2010. doi: 10.1080/02697459.2010.511016

- ARUP, Cities. Shaping a better world by shaping cities, 2014.

- J. Gavinha, D. Sui, “Crecimiento inteligente-breve historia de un concepto de moda en Norteamérica”, Scripta Nova, 7(46), 39, 2003.

- D. Godschalk, “Land use planning challenges. Coping with Conflicts in Visions of Sustainable Development and Livable Communities”, Journal of the American Planning Association, 70(1), 5-13, 2004. doi.org/10.1080/01944360408976334

- P. Katz, The New Urbanism: Toward an Architecture of Community. McGraw-Hill, 1994.

- S. Wheeler, Planning for Sustainability, Routledge, 2013.

- Congress for the new urbanism, “Canons of Sustainable Architecture and Urbanism”, 2011.

- Ecocity Builders, “Why eco-cities”, 2014.

- E. Moreno, “Indicadores para el estudio de la sustentabilidad urbana en Chimalhuacán, Estado de México”, Estudios Sociales, 22(43), 161-186, 2013. doi.org/10.24836/es.v22i43.51

- L. Farias, El transporte público urbano bajo en carbono en América Latina. Innovación ambiental de servicios urbanos y de infraestructura: hacia una economía baja en carbono. CEPAL-Naciones Unidas, 2012.

- Eco-inteligencia, Estocolmo, referente de sostenibilidad, 2011.

- Comisión Europea, Ciudades del mañana-Retos, visiones y caminos a seguir. Unión Europea, 2011.

- C. Henríquez, Modelando el crecimiento de ciudades medias. Hacia un desarrollo urbano sustentable, Ediciones UC, 2014.

- J. Michelini, C. Davies, “Ciudades intermedias y desarrollo territorial; un análisis exploratorio del caso argentino”, Documentos de Trabajo GEDEUR, 5, 1-26, 2009.

- J. Ganau, J. Vilagrasa, “Ciudades medias en España: posición en la red urbana y procesos urbanos recientes”, Mediterráneo Económico, 3, 37-73, 2003.

- R. Brunet, “Des villes comme Lleida. Place et perspectives des villes moyennes en Europe”, Bellet, C. y Llop, J. M. (comp), Ciudades Intermedias. Urbanización y sostenibilidad. Lleida, Milenio. 108-124, 2000.

- C. Bellet, J. Llop, “Miradas a otros espacios urbanos”, Scripta Nova, 8(165), 1- 30, 2004.

- C. Bellet, E. Olazabal, “Formas de crecimiento urbano de las ciudades medias españolas en las últimas décadas”, Terr@ Plural, Ponta Groosa, 14, 1-19, 2020. doi: 10.5212/TerraPlural.v.14.2013229.013

- G. Salazar, F. Irarrázaval, M. Fonck, “Ciudades intermedias y gobiernos locales: desfases escalares en la Región de La Araucanía, Chile”, EURE, 43(130), 161-184, 2017. doi.org/10.4067/s0250-71612017000300161

- A. Borsdorf, “Cómo modelar el desarrollo y la dinámica de la ciudad latinoamericana”, EURE, 29(86), 37-49, 2003. doi.org/10.4067/S0250-71612003008600002

- A. Borsdorf, R. Hidalgo, “Städtebauliche Megaprojekte im Umland lateinamerikanischer”, Geographische Rundschau, 57(10), 30-39, 2005.

- J. Bähr, A. Borsdorf, “La ciudad latinoamericana. La construcción de un modelo Vigencia y perspectivas”, Ciudad, urbanismo y paisaje, 2(2), 207-222, 2005.

- F. Sabatini, G. Cáceres, J. Cerda, “Segregación residencial en las principales ciudades chilenas: tendencias de las tres últimas décadas y posibles cursos de acción”, Eure, 27(82), 21-42, 2001. doi.org/10.4067/S0250-71612001008200002

- C. De Mattos, “Globalización, negocios inmobiliarios y transformación urbana”, Nueva Sociedad, 212, 82-96, 2007.

- J. Hernández, B. Martínez, J. Méndez, “Reconfiguración territorial y estrategias de reproducción social en el periurbano poblano”, Cuadernos de Desarrollo Rural, 2(74), 13-34, 2014. doi:10.11144/javeriana.CRD11-74.rter

- O. Figueroa, “Transporte urbano y globalización. Políticas y efectos en América Latina”, Eure, 31(94), 41-53, 2005. http://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0250-71612005009400003

- J. Da Cunha, J. Rodríguez, “Crecimiento urbano y movilidad en América Latina”, Latinoamericana de Población, 3(4-5), 27-64, 2009. doi: 10.31406/relap2009.v3.i1.n4-5.1

- ONU, Estado de las ciudades de América Latina y el Caribe. ONU-Habitat, 2010.

- B. Iglesias, “Las ciudades intermedias en la integración terriotiral del Sur Global”, Revista CIDOB d´Afers Internacionals, 114, 9-132, 2016. doi.org/10.24241/rcai.2016.114.3.109

- Fundación Idea, SIMO Consulting y Cámara de Senadores, México compacto: Las condiciones para la densificación urbana inteligente en México, 2014.

- J. Castillo, E. Patiño, “Ciudades medias”, Elementos, Ciencia y Cultura, 6(34), 29-33, 1999.

- G. Álvarez, “El crecimiento urbano y estructura urbana en las ciudades medias mexicanas” Quivera, 12(2), 94-114, 2010.

- C. Göbel, “Una visión alemana de los modelos de ciudad. El caso de Querétaro”, Gremium, 2(4), 47-60, 2015.

- INEGI, Panorama sociodemográfico de Hidalgo 2015, Encuesta Intercensal. INEGI, 2015.

- SEDESOL, La expansión de las ciudades 1980-2010. México 135 ciudades. SEDESOL, 2012.

- A. Aguilar, I. Escamilla, Peri-urbanización y sustentabilidad en grandes ciudades, Porrúa 2011.

- E. Villegas, “Las Unidades de Planificación y Gestión Territorial como Directriz para la Zonificación Urbana”, El Ágora-U.S.B., 14(2), 551-581, 2014. doi.org/10.21500/16578031.67

- C. Pérez, “Expansión de la ciudad en la zona metropolitana de Pachuca: procesos desiguales y sujetos migrantes e inmobiliarios”, Territorios, 38, 41-65, 2018. doi.org/10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/territorios/a.5577

- Índice de competitividad Urbana (IMCO), ¿Quién manda aquí?, IMCO, 2014.

- J. M. Fernández-Güell, Planificación estratégica de ciudades: Nuevos instrumentos y procesos 10, Reverté Segunda edición, 2019.

- A. Posada-Arrubla, Á. D. Paredes-Buitrago, G. E. Ortiz-Romero, “Enfoque sistémico aplicado al manejo de parques metropolitanos, una posición desde Bogotá DC-Colombia”, Revista UDCA Actualidad & Divulgación Científica, 19(1), 207-217, 2016.

- L. Von Bertalanffy, Teoría general de los sistemas. Limusa, 1996.

- J. P. Van Gigch, “General systems theory”, Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 14(2), 149-150, 1997.

- O. Gelman, G. Negroe, “Papel de la planeación en el proceso de conducción” Boletín IMPOS, Instituto Mexicano de Planeación y Operación de Sistemas, 11(61), 1-17, 1981.

- A. Miguel, J. Torres, P. Maldonado, Fundamentos de la planeación urbano-regional. México; Instituto Municipal de Investigación y Planeación de Ensenada (IMIP), 2011.